Odysseus (/oʊˈdɪsiəs, oʊˈdɪsjuːs/; Greek: Ὀδυσσεύς [odysˈsews]), also known by the Latin name Ulysseus (US /juːˈlɪsiːz/, UK /ˈjuːlɪsiːz/; Latin: Ulyssēs, Ulixēs), was a legendary Greek king of Ithaca and the hero of Homer's epic poem the Odyssey. Odysseus also plays a key role in Homer's Iliad and other works in that same epic cycle.

Husband of Penelope, father of Telemachus, and son of Laërtes and Anticlea, Odysseus is renowned for his brilliance, guile, and versatility (polytropos), and is hence known by the epithet Odysseus the Cunning (mētis, or "cunning intelligence"). He is most famous for the ten eventful years he took to return home after the decade-long Trojan War.

Nikos Kazantzakis' The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel, a 33,333 line epic poem, begins with Odysseus cleansing his body of the blood of Penelope's suitors. Odysseus soon leaves Ithaca in search of new adventures. Before his death he abducts Helen, incites revolutions in Crete and Egypt, communes with God, and meets representatives of such famous historical and literary figures as Vladimir Lenin, Don Quixote and Jesus.

James Joyce's novel Ulysses uses modern literary devices to narrate a single day in the life of a Dublin businessman named Leopold Bloom. Bloom's day turns out to bear many elaborate parallels to Odysseus' twenty years of wandering.

In Virginia Woolf's response novel Mrs Dalloway the comparable character is Clarisse Dalloway, who also appears in The Voyage Out and several short stories.

...a shorthand term for modern society, or industrial civilization. Portrayed in more detail, it is associated with (1) a certain set of attitudes towards the world, the idea of the world as open to transformation, by human intervention; (2) a complex of economic institutions, especially industrial production and a market economy; (3) a certain range of political institutions, including the nation-state and mass democracy. Largely as a result of these characteristics, modernity is vastly more dynamic than any previous type of social order. It is a society—more technically, a complex of institutions—which, unlike any preceding culture, lives in the future, rather than the past (Giddens 1998, 94).

The era of modernity is characterised socially by industrialisation and the division of labour and philosophically by "the loss of certainty, and the realization that certainty can never be established, once and for all" (Delanty 2007). With new social and philosophical conditions arose fundamental new challenges. Various 19th-century intellectuals, from Auguste Comte to Karl Marx to Sigmund Freud, attempted to offer scientific and/or political ideologies in the wake of secularisation. Modernity may be described as the "age of ideology." (Calinescu 1987, 2006).

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo and others developed a new approach to physics and astronomy which changed the way people came to think about many things. Copernicus presented new models of the solar system which no longer placed humanity's home, on Earth, in the centre. Kepler used mathematics to discuss physics and described regularities of nature this way. Galileo actually made his famous proof of uniform acceleration in freefall using mathematics (Kennington 2004, chapt. 1,4).

Francis Bacon, especially in his Novum Organum, argued for a new experimental based approach to science, which sought no knowledge of formal or final causes, and was therefore materialist, like the ancient philosophy of Democritus and Epicurus. But he also added a theme that science should seek to control nature for the sake of humanity, and not seek to understand it just for the sake of understanding. In both these things he was influenced by Machiavelli's earlier criticism of medieval Scholasticism, and his proposal that leaders should aim to control their own fortune (Kennington 2004, chapt. 1,4).

Influenced both by Galileo's new physics and Bacon, René Descartes argued soon afterward that mathematics and geometry provided a model of how scientific knowledge could be built up in small steps. He also argued openly that human beings themselves could be understood as complex machines (Kennington 2004, chapt. 6).

Isaac Newton, influenced by Descartes, but also, like Bacon, a proponent of experimentation, provided the archetypal example of how both Cartesian mathematics, geometry and theoretical deduction on the one hand, and Baconian experimental observation and induction on the other hand, together could lead to great advances in the practical understanding of regularities in nature (d'Alembert 2009 [1751]; Henry 2004).

- increased movement of goods, capital, people, and information among formerly discrete populations, and consequent influence beyond the local area

- increased formal social organization of mobile populaces, development of "circuits" on which they and their influence travel, and societal standardization conducive to socio-economic mobility

- increased specialization of the segments of society, i.e., division of labor, and area inter-dependency

- increased level of excessive stratification in terms of social life of a modern man

- Increased state of dehumanisation, dehumanity, unionisation, as man became embittered about the negative turn of events which sprouted a growing fear.

- man became a victim of the underlying circumstances presented by the modern world

- Increased competitiveness amongst people in the society (survival of the fittest) as the jungle rule sets in.

Constantine P. Cavafy (/kəˈvɑːfɪ/; also known as Konstantin or Konstantinos Petrou Kavafis, or Kavaphes; Greek: Κωνσταντίνος Π. Καβάφης; April 29 (April 17, OS), 1863 – April 29, 1933) was an Ethnic Greek poet who lived in Alexandria and worked as a journalist and civil servant. He wrote 154 poems; dozens more remained incomplete or in sketch form. During his life, he consistently refused to formally publish his work and preferred to share them through local newspapers and magazines, or even print them out himself and give them away to anyone interested. His most important poetry was written after his fortieth birthday and officially published two years after his death. His work was internationally recognised, as several of them were translated in other languages.

Cavafy was born in 1863 in Alexandria, Egypt, to Greek parents, and was baptized into the Greek Orthodox Church. His father's name was Πέτρος Ἰωάννης, Petros Ioannēs —hence the Petrou patronymic (GEN) in his name— and his mother's Charicleia (Greek: Χαρίκλεια; née Γεωργάκη Φωτιάδη, Georgakē Photiadē). His father was a prosperous importer-exporter who had lived in England in earlier years and acquired British nationality. After his father died in 1870, Cavafy and his family settled for a while in Liverpool in England. In 1876, his family faced financial problems due to the Long Depression of 1873, so, by 1877, they had to move back to Alexandria.

In 1882, disturbances in Alexandria caused the family to move again, though temporarily, to Constantinople. This was the year when a revolt broke out in Alexandria against the Anglo-French control of Egypt, thus precipitating the 1882 Anglo-Egyptian War. Alexandria was bombarded by a British fleet, and the family apartment at Ramleh was burned.

In 1885, Cavafy returned to Alexandria, where he lived for the rest of his life. His first work was as a journalist; then he took a position with the British-run Egyptian Ministry of Public Works for thirty years. (Egypt was a British protectorate until 1926.) He published his poetry from 1891 to 1904 in the form of broadsheets, and only for his close friends. Any acclaim he was to receive came mainly from within the Greek community of Alexandria. Eventually, in 1903, he was introduced to mainland-Greek literary circles through a favourable review by Xenopoulos. He received little recognition because his style differed markedly from the then-mainstream Greek poetry. It was only twenty years later, after the Greek defeat in the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922), that a new generation of almost nihilist poets (e.g. Karyotakis) would find inspiration in Cavafy's work.

A biographical note written by Cavafy reads as follows:

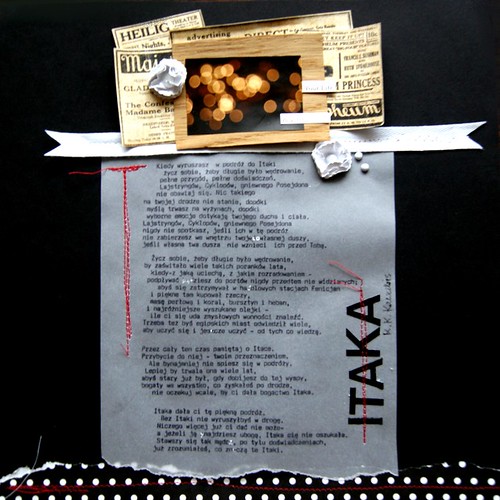

In 1911, Cavafy wrote Ithaca, inspired by the Homeric return journey of Odysseus to his home island, as depicted in the Odyssey. The poem's theme is that enjoyment of the journey of life, and the increasing maturity of the soul as that journey continues, are all the traveler can ask for. To Homer, and to the Greeks in general, not the island, but the idea of Ithaca is important. Life is also a journey, and everyone has to face difficulties like Odysseus, when he returned from Troy. When you reach Ithaca, you have gained so much experience from the voyage, that it is not very important if you reached your goals (e.g. Odysseus returned all alone). Ithaca cannot give you riches, but she gave you the beautiful journey.

Almost all of Cavafy's work was in Greek; yet, his poetry remained unrecognized in Greece until after the publication of his first anthology in 1935. He is known for his prosaic use of metaphors, his brilliant use of historical imagery, and his aesthetic perfectionism. These attributes, amongst others, have assured him an enduring place in the literary pantheon of the Western World.